NYPD Use of Force Reporting Guide

When officers use force, they must report it in the NYPD's "Finest Online Records Management System" where police violence is tracked

This is day two in the “NYPD Docs Clearinghouse” week. Check out yesterday’s post, and come back every day this week for new NYPD docs daily.

The Document:

Few things ruin a good day more than police violence. Everybody knows it. That’s why department regulations mandate that every police use of force be reported, categorized, and investigated by police supervisors. Force causes not only bruises, but mountains of paperwork.

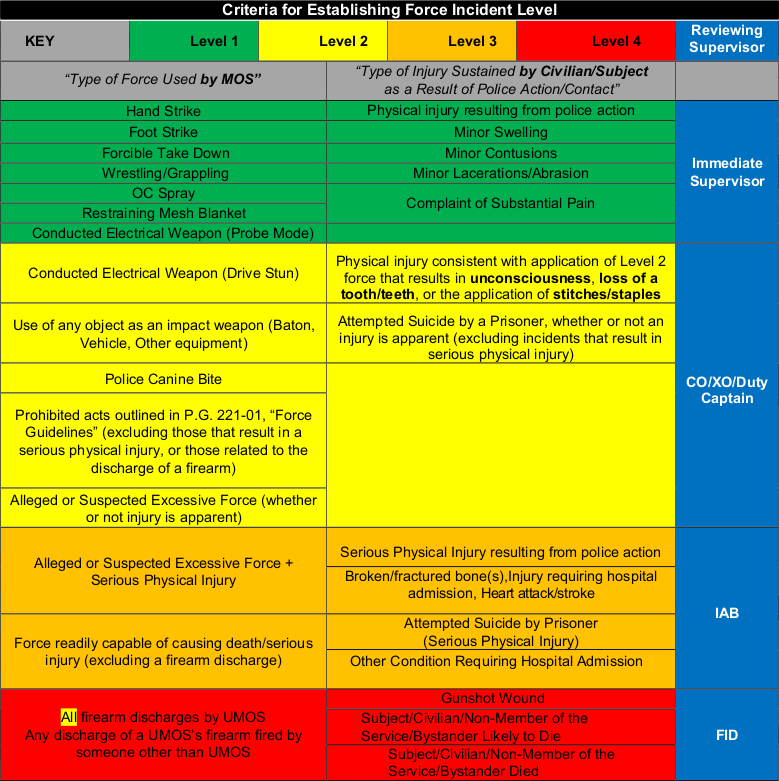

The Use of Force Reporting Guide, prepared October 2019, prescribes the nuances of how police violence is tracked internally at NYPD, and what happens in its aftermath. Each instance of used force is (supposed to be) recorded in a “Threat, Resistance or Injury Interaction Report,” abbreviated TRI, and assigned a severity level from 1 to 4. The higher levels represent the more violent or consequential interactions, with higher disciplinary stakes.

Although the guide comes with the caveat that it “does not describe every possible permutation of the use‐of‐force spectrum, which includes too many possibilities to recount in a short guide,” at 52 pages, it describes the levels of force as follows.

Level one, includes hand strikes, foot strikes, forcible take down, grappling, and OC spray. The resulting injuries may include minor swelling, lacerations, and “complaint of substantial pain.” These incidents are investigated by an officer’s immediate supervisor, such as their sergeant or lieutenant.

Level two, includes stun gun discharge, use of impact weapons, canine bite, prohibited acts, and alleged excessive force. Injuries may cause unconsciousness, the loss of a tooth, or the necessity for stitches or staples. Attempted prisoner suicide also falls under this category, so long as the attempt does not result in serious injury. These are investigated by commanding or executive officers.

Level three is where potentially deadly use of force comes into play. It includes any police act “readily capable” of causing death or serious injury, excluding firearms discharge, and any alleged excessive force which results in serious injury. These injuries may break bone, affect heart attack, or require hospitalization. If a prisoner’s suicide attempt causes grave harm, it is also in this level. These incidents are investigated by the much-feared Internal Affairs Bureau (colloquially, but not endearingly, called the “rat squad” by police officers).

Level four use of force covers any firearms discharge of a cop’s weapon, even if the triggerman is not a police officer. The injuries categorized here are self evident: gunshot wounds, and death. These incidents are investigated by the Force Investigation Division, FID.

At its discretion, Internal Affairs can step in to investigate any lower level TRI incidents. However, FID may supersede Internal Affairs if it chooses. If this happens, it means the police officers involved are having a very bad day, and are probably seeking the counsel of their union rep. (It probably also means the recipient of said force is also having a bad day.)

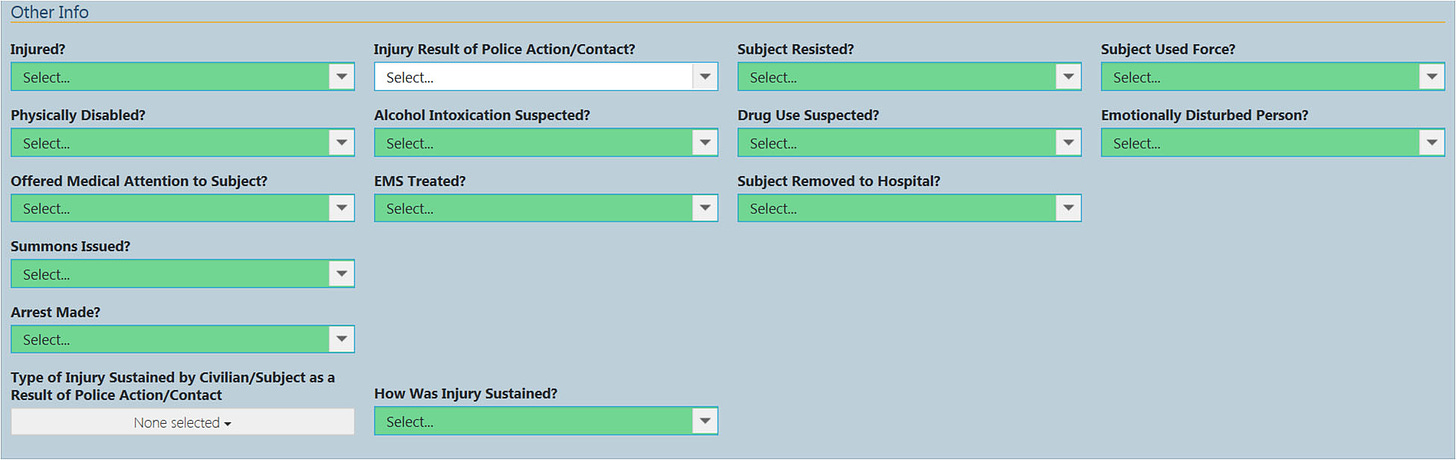

The TRI reports are created in a database called the “Finest Online Records Management System,” or FORMS, which unifies certain of NYPD’s digital data assets. The TRI reports can be entered into FORMS straight from a department-issue smartphone, tablet, or computer terminal. The guide includes instructions and screenshots for how to use the FORMS software to correctly enter the TRI data and manage the TRI report through its life cycle. Each member of the NYPD has a FORMS account, which includes a FORMS Inbox, through which officers receive notifications, sometimes requiring them to act, for instance, if a TRI indicated that they were a witness to a use of force.

At a TRI report’s conclusion, the supervisor finalizing the report may make note of any tactical recommendations or “creative approaches” to consider in hindsight. And they have the option to refer the case to Internal Affairs or FID, most likely if misconduct is suspected.

Interestingly, officer’s certain use of force off-duty, even out-of-state on vacation, is still required to be entered into FORMS. The guide gives an example of an officer on vacation with his family and friends in Maine. The officer’s dumb friend goes rifling through his bedroom drawer. He finds the cop’s gun and plays with it before accidentally lodging a bullet in the floor. No one is hurt, but the guide states that this incident should be reported as a level four TRI. (It’s also likely that this officer has poor taste in friend.)

But even the finest Finest data systems are only as useful as the data is accurate or exists at all. The NYPD makes some aggregations of the TRI data public, and has released an annual Use of Force report for every year since 2007. Except notably for 2020 – the year of the mass protests for which the NYPD was roundly criticized for its brutality. Although we don’t have the 2020 report, an analysis of other TRI-based NYPD data reveals at least 207 reported crowd control uses of force between May and July, the peak of last summer’s unrest.

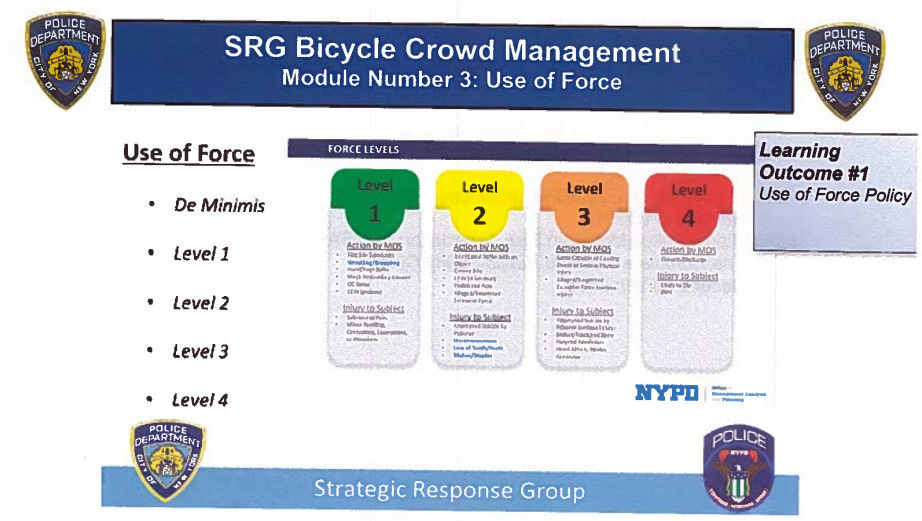

Finally, no analysis of NYPD policy is complete without discussing its riot squad, the Strategic Response Group. Although the Use of Force Reporting Guide only recognizes the above stated four levels, the SRG training materials, first published in The Intercept, adhere to these four plus one more. The SRG recognizes a level called “de minimis” which is not required to be reported. This includes “guiding a person to the ground,” or “the mere use of equipment,” such as – incredibly – the “mobile fence line with bicycle.” (Discussion of the Mobile Fence Line formation is beyond the scope of this writing, but you can read about it in The Intercept)

Tune in tomorrow for day three of the NYPD Docs Clearinghouse!